1. President Shalala recently announced an increase in wages and affordable health benefits for all contract employees, so why aren’t the UNICCO workers satisfied with this and back at work?

Who wouldn’t be pleased with increased compensation? Although the new compensation is still considerably below the Miami-Dade living wage (see the Faculty Senate report for a fuller explanation), the workers we talk to are uniformly gratified to see increased wages. Nonetheless, they didn’t go on strike to achieve this goal. They are on strike to protest unfair labor practices by their employer.

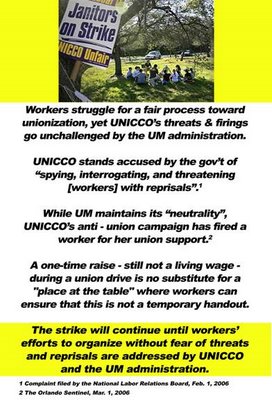

After investigating charges made by the workers, in January the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) found that there was “reasonable cause to believe” that the charges were true and issued a complaint (tantamount to an indictment in labor law) alleging that UNICCO violated US labor law by committing the following unfair labor practices:

Interrogating workers about their union support;

Prohibiting them from talking about the union at work;

Forcing them to sign a statement disavowing the union;

Accusing them of disloyalty for participating in off-hours union functions;

Threatening reprisals against union supporters;

Conducting unlawful surveillance of a union meeting.

A hearing is scheduled for the end of May but may be delayed owing to new charges now under investigation by the NLRB relating to UNICCO’s firing of one of the leading union supporters after she gave an interview to a journalist writing a story about the union campaign.

And the intimidation has increased since President Shalala’s announcement of improved wages. The Rev. Frank Corbishley (Chaplain at the Chapel of the Venerable Bede on the Gables campus) wrote to the South Florida Interfaith Committee for Worker Justice: “One worker told me that last Saturday [18 March] UNICCO called him 17 times, pressuring him to return to work. Many workers receive phone calls from their UNICCO supervisors, some threatening to fire the workers if they do not return to work.” Additionally, striking workers have reported threats from UNICCO that they may forfeit to return the new raise if they don’t return to work, and non-striking workers have threatened with firing if they don’t publicly endorse an NLRB election.

2. Now that they’ve received an improved compensation package, do the workers still want to unionize?

We won’t know for certain how many workers want to unionize until they are allowed to express their views in a manner of their choosing. Nonetheless, there are a number of faculty who have had multiple conversations on the subject with UNICCO workers whom they know either from years of living on campus or from research they have been doing on immigrant populations in South Florida. And the faculty in question report that the workers uniformly express support for unionization. The issues that concern the workers relate not just to compensation but to their working conditions, their right to be treated with dignity, and their right to have a voice in future decisions that affect their working lives. We certainly don’t think we can speak for even the workers we know, however, and would rather they do so for themselves. Indeed, you may read some of their comment here, and we invite you to meet with the workers to hear their views and to ask questions. We will arrange a meeting for faculty and workers during the week of April 3rd.

3. If the University administration was able to improve compensation for the workers, is a union really needed?

Again, that’s for the workers to decide. We point out, however, that the Faculty Senate and undergraduate student government urged the administration to offer a living wage to the workers in 2001, but the administration did nothing to address compensation for well over four years. The administration’s largesse only came with the threat of unionization and the pressure of public opinion, and there’s no guarantee that there will be future improvements without continued pressure. Without the ability to negotiate for themselves, the workers have little way to guarantee further salary increases or appropriate affordable health coverage (what the UM administration or contractors consider affordable may not be viewed as such by the workers), much less safe working conditions and respect in the work place. While the faculty may not be unionized, we have well-defined and long-standing rights, privileges and obligations, and mechanisms in place to defend these, all outlined in the Faculty Manual. We also have representation that we select to negotiate with the administration on issues relating to salaries, health care, retirement, job security, working conditions, etc. Shouldn’t the workers have the same rights we enjoy?

4. OK, if the workers want a union, why are they insisting on a card check instead of an NLRB election? After all, UNICCO says it’s willing to have an NLRB election.

There are multiple answers to this question. First and at present foremost, the NLRB will not conduct an election, even if the workers agree that this is an acceptable resolution, until the NLRB complaint against UNICCO is heard and resolved. So, UNICCO’s call for an NLRB election is more than a bit disingenuous. Even if an election were possible, though, the workers would unquestionably insist on a card check simply because they view it as a fairer and less threatening process. The election process allows for greater intimidation by the employer than the card check process, as revealed by numerous studies. In a recent study whose results were released last week, two professors at Rutgers and Wheeling Jesuit University conducted a telephone survey of workers at sites where employees sought to unionize using NLRB elections or card check campaigns. The respondents included workers who had voted for and against the union and were from campaigns in which the union won and lost. The findings are revealing with regards to NLRB elections and card check campaigns:

Workers in NLRB elections were twice as likely (46% vs. 23%) as those in card check campaigns to report that management coerced them to oppose the union.

Workers in NLRB elections were 53% more likely than those in card check campaigns to report that management threatened to eliminate jobs, and 28% more likely to report that management discriminated against union supporters.

Fewer workers in card check campaigns than in elections felt pressure from coworkers to support the union (17% vs. 22%). Fewer than one in twenty (4.6%) workers who signed a card with a union organizer reported that the presence of the organizer made them feel pressured to sign the card.

Workers in card check campaigns were almost twice as likely as those in elections (62% vs. 33%) to report that management took a neutral position and left the decision to form a union up to workers. [1]

This survey complements the alarming findings of a 2005 study published by the University of Chicago’s Center for Urban Economic Development. [2] That study showed that in 62 union campaigns conducted in Chicago in 2002:

30% of employers fire pro-union workers.

49% of employers threaten to close a worksite when workers try to form a union.

51% of employers coerce workers into opposing unions with bribery or favoritism.

82% of employers hire union-busting consultants to fight organizing drives.

91% of employers force employees to attend one-on-one anti-union meetings with supervisors.

One of the study’s co-authors, Nik Theodore, confirms that the “research clearly shows that firings, bribes, and threats are pervasive and that these actions greatly impede workers’ ability to form unions.” [3] In reviewing the pros and cons of NRLB elections vs. card check campaigns, Steven Greenhouse cites the following example in a recent New York Times article:

At the Consolidated Biscuit bakery in McComb, Ohio, Bill Lawhorn said more than 70 percent of the workers had signed cards in favor of joining the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers Union when he led efforts to form a union in 2002. Nonetheless, the union lost a secret-ballot election, 485 to 286, after Consolidated Biscuit conducted a vigorous anti-union campaign. Two years later a National Labor Relations Board judge found that managers had illegally spied on union supporters and had warned them that the bakery would go bankrupt if a union was voted in. Mr. Lawhorn was fired the day after the unionization vote. The labor board judge ordered him and six other workers reinstated, ruling that they were illegally fired for supporting a union.” [4]

Given the evidence, were you a UNICCO worker, would you prefer an NLRB election or a card check campaign? We think the answer is clear.

A final point: NLRB elections are inordinately slow processes. In the typical case, it takes weeks or even months for the agency to schedule an election, and the post-election appeals process can take two to three years. To cite a local example from a previous FAQ, the NLRB conducted an election at Pan American Hospital in 2004 in which fully 97% of the employees voted for unionization, but it took the agency nine months to certify the results, and – more than two years after the election -- the employer has yet to agree to a contract.

As we have learned from recent elections in Florida, democracy is messy. It ought not be this messy, though.

5. Still, isn’t an NLRB election a more democratic process?

No. For a union to be selected in an NLRB election, only a majority of those voting is required. A card check campaign requires that a majority of those eligible to vote support a union before it may be selected. So, for a union to be selected in a card check campaign, a greater number of workers must actually indicate their preference for the union than is required for an NLRB election. [5] Additionally, we regularly join organizations that represent our views by signing up instead of voting. As Bruce Raynor, President of Unite Here (a union representing restaurant, hotel and apparel workers), notes: “''A worker can join a church or synagogue or the Republican Party by signing a card. That's how people join organizations in the United States. The idea that workers can't join a union by signing their name is ludicrous.'' [6] And UNICCO has allowed card check campaigns in lieu of NLRB elections for workers wanting to unionize at other sites. Why is Unicco now claiming that the process is undemocratic and insisting that UNICCO workers at UM participate in an NLRB election?

6. How often is a card check campaign used instead of an NRLB election, and why do employers object to them?

Card check agreements have been around for a long time and are a legal, recognized process for union formation. Not all employers object to card check campaigns, which are now more frequent than NLRB elections. According to the previously cited New York Times article, card check campaigns have been used to sign up about 70% of the workers who unionized last year: “150,000 private-sector workers joined unions in 2005. Over the past year, the procedure has been used to unionize 4,600 workers at the Wynn Las Vegas hotel-casino, 5,000 janitors in Houston and 16,500 workers at Cingular, the cell phone company.” There are also advantages to employers in using card check campaigns, including:

Significant reduction of expensive and lengthy conflicts that surround NLRB elections.

Adding value to the business.

Securing or expanding the customer base who care about the unionization of the firm.

Ability of the union to supply qualified, skilled labor. [7]

[1] “Fact over Fiction: Opposition to Card Check Doesn’t Add Up,” American Rights at Work.

[2] Chirag Mehta and Nik Theodore, Undermining the Right to Organize: Employer Behavior During Union Representation Campaigns, Center for Urban Economic Development, U of Illinois: December 2005.

[3] “Widespread Use of Firings, Bribes, and Threats by Employers: New union-busting data released by American Rights at Work,” 6 December 2005 Press Release, American Rights at Work.

[4] Steven Greenhouse, “Employers Sharply Criticize Shift in Unionizing Method to Cards from Elections,” The New York Times, 11 March 2006.

[6] Steven Greenhouse, “Employers Sharply Criticize Shift in Unionizing Method to Cards from Elections,” The New York Times, 11 March 2006.

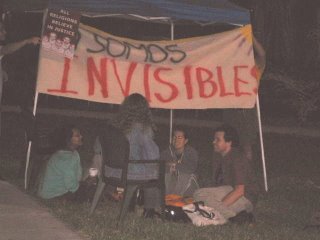

a little after 8 pm president shalala agrees to meet with the students on their own turf, with only one condition: that father corbishley be out of the room. after a longish deliberation, the group rejects the condition. the students feel too vulnerable without father corbishley in the room and the police surrounding them. more time passes. eventually the students agree to have father corbishley sit just outside the admissions office, in the ashe building lobby, allowed to re-enter the moment the meeting with the president is over. a series of meetings starts. the students and the president meet for 30 or 40 minutes, then break, then meet again.

a little after 8 pm president shalala agrees to meet with the students on their own turf, with only one condition: that father corbishley be out of the room. after a longish deliberation, the group rejects the condition. the students feel too vulnerable without father corbishley in the room and the police surrounding them. more time passes. eventually the students agree to have father corbishley sit just outside the admissions office, in the ashe building lobby, allowed to re-enter the moment the meeting with the president is over. a series of meetings starts. the students and the president meet for 30 or 40 minutes, then break, then meet again.

here are the exact words of the statement issued by the university and read by tanya and mewelau:

here are the exact words of the statement issued by the university and read by tanya and mewelau: